This third week of “real podcasting,” I’m still too overwhelmed with learning audio stuff to hardly work on writing my novels. Nonetheless, it’s heartening to learn new pod things. (See more about Podcast #1 h-e-r-e and Podcast #2 h-e-r-e.) This whole endeavor brings me closer to accomplishing my writing goal of eventually making audio show episodes out of my books. Plus, a few days ago I was invited to be a guest on someone else’s podcast!

Now that I’m officially a “podcaster,” I recently entered a Spotify competition that promised training, financial support, travel, publicity, and meetings with movers and shakers. Contests generally aren’t my thing, but this one didn’t charge a fee, and since they didn’t advertise it for long, I though I might have a chance at winning.

How do you feel about labels? Do you have one? Or more?

The competition was for “LatinX” podcasters, a term that’s expansive. If I understand it correctly, “LatinX” goes beyond gender, sexuality, and which country one’s parents are from. I’m ambivalent about labels, worried that they separate and compartmentalize us. On the other hand, there’s strength to be found in labeling when it comes to banding together for social justice.

Here’s how I filled in Spotify’s contest form:

Contest Question #1 was: “What does being LatinX living in the US mean to you?”

I grew up as a Latin/Spanish-speaking X/outsider in all of fifteen homes and schools— the “Latin” and the “X” tamped into one fair-skinned LatinX girl who was bullied for the sin of chubbiness, and who couldn’t fathom why she and her mom were treated so very differently from the family males.

My father was a charismatic Spaniard who doomed me to find a husband from Spain, bear children, stay home, look sexy, and turn a blind eye when my inevitable husband would inevitably stray. Sissy work was off-limits for the boys. Dad groomed them for machismo, to become bullfighters or flamenco guitarists or tennis pros.

At four-years-old, already I pondered nature vs. nurture vs. culture. Males had enough respect to create an ache in child-me, one I was sure I wouldn’t have if I were a boy. If I could have regressed clear to before my father’s spermatozoon collided with the ovum inside my Argentine mom’s womb, I would have switched genders.

When it came to speaking Spanish, as a green-eyed auburn-haired kid, I found it hard to be taken seriously because I didn’t fit what adults thought Latinos ought to look like. At the same time, I wondered lines on maps mattered so much. The politicians the grownups would discuss argued a lot about lines on sand and dirt and blood and gender, but none actually fought in the wars they made.

Contest Question #2 requested an “elevator pitch,” which should be a 50-word proposal for the kind of show I wanted to produce.

Right before I clicked “send,” I read Spotify’s “Terms and Conditions.” If I proposed to do a show based on my novels, would I sign over control to my books? After a night of having decided to not participate, the next morning I offered them a different proposed show. Here’s my revamped “elevator pitch”:

My podcast would fill the crevices where nitty gritty day-to-day exists. Stories un-beribboned with pat answers. Characters who go beyond the archetypical, and are more akin to annoying diverse friends who are there when we need them — or maybe they aren’t, but are later.

For Contest Question #3, I needed to go into more depth regarding that proposed show. I answered by saying:

My serialized fiction podcast intends to bring forth characters as unique and complex as life, who’ll help us exist more harmoniously. So much of what we hear, read, and watch is populated by the symmetrical and the able-bodied, the fertile and the virile. All of them are one-dimensional people who are invariably destined for parenthood and partnering.Where are the “X’s,” LatinX included?

My shows will glory in our convoluted humanity. It’s fine to not be a heroine or a hero, neither a goddess nor a god. It’s ok when we misunderstand ourselves. Even mirrors lie, and even selfies are no more than seized flashes of light, color, and shadow.

Listeners will be enticed to take a second eyeful, at each other. Whereas the self-help industry encourages us to change ourselves, this show would spotlight what’s uniquely wonderful about us.

Fiction nourishes our souls. Fiction is the treasure map “X marks the spot” of celebrating our nuances.

Our veins of gold aren’t found by pretending we’re smarter than we are. Platinum manifests when we voice our vulnerabilities. Revealing “This is me, from the inside out,” gets everyone closer to, “This is us.”

It’s time, readers, to meet Judith Barrow…

Judith has published eight novels, and writes much more than books. She blogs from her home in West Wales, England. H-e-r-e you can find out about her. Read on for her experience and thoughts on writing (you can also listen to a podcast of it h-e-r-e, and watch a video of it h-e-r-e …

Judith Barrow on How She Publishes and Writes

(For an audio version of this post, click H-E-R-E.)

I wrote for years before letting anyone read my work. If I was self-deluded; if it was rubbish, I didn’t want to be told. I enjoyed my “little hobby” (as it was once described by a family member). But then I began to enter my short stories into competitions. Sometimes I was placed, once or twice I even won. Encouraged, I moved on to sending to magazines — I had some luck, was published – once! But I hadn’t dared to send out cny of the fourc full length book manuscripts I’d written (and actually never did, they were awful!) That changed after a long battle with brcast cancer in my forties and, finally finishing a book that I thought might possibly…possibly, be cood enough for someone else to see, other than me, I took a chance.

I grew resigned (well almost) to those A4 self-addressed envelopes plopping through the letterbox. (Yes, it was that long ago!) The weekly wail of ‘I’ve been rejected again,’ was a ritual that my long-suffering husband also (almost) grew resigned to.

There were many snorts of exasperation at my gullibility and stubbornness from the writing group I was a member of at the time. They all had an opinion — I was doing it all wrong. Instead of sending my work to publishers I should have been approaching agents.

‘You’ll get nowhere without an agent,’ one of the members said. She was very smug. Of course, she was already signed up with an agent whose list, she informed me, was full.

‘How could you even think of trying to do it on your own?’ was another horrified response when told what I’d done, ‘With the sharks that are out there, you’ll be eaten alive.’

‘Or sink without a trace.’ Helpful prediction from another so-called friend.

So, after trawling my way through the Writers & Artists Yearbook (an invaluable tome) I bundled up two more copies of my manuscript and sent them out to different agents

Six months later I was approached by one of the agents who, on the strength of my writing, agreed to take me. The praise from her assistant was effusive, the promises gratifying. It was arranged that I meet with the two of them in London to discuss the contract they would send in the post, there would be no difficulty in placing my novel with one of the big publishers; they would make my name into a brand.

There was some editing to do, of course. Even though the manuscript was in its fifth draft, I knew there would be. After all, the agent, a big fish in a big pond, knew what she was doing. Okay, she was a little abrasive (on hindsight I would say rude) but she was a busy person, I was a first-time author.

But I was on my way. Or so I thought.

A week before the meeting I received an email; the agent’s assistant had left the agency and they no longer thought they could act for me. They had misplaced my manuscript but would try to locate it. In the meantime, would I send an SAE for its return when/if ‘it turned up’?

So — back to square one.

For a month I hibernated (my family and friends called it sulking, but I preferred to think of it as re-grouping). I had a brilliant manuscript that no one wanted (at this point, I think it’s important to say that, as an author, if you don’t have self-belief ,how can you persuade anyone else to believe your work is good?) But still, no agent, no publisher.

There were moments, well weeks (okay, if I’m honest — months), of despair, before I took a deep breath and resolved to try again. I printed out a new copy of the novel. In the meantime, I trawled through my list of possible agents. Again.

Then, out of the blue, a phone call from the editorial assistant who’d resigned from that first agency to tell me she’d set up her own, was still interested in my novel and could we meet in London in a week’s time? Could we? Try and stop me, I thought.

We met. Carried away with her enthusiasm for my writing, her promises to make me into a ‘brand name’ and her assurance that she had many contacts in the publishing world that would ‘snap her hand off for my novel’, I signed on the dotted line.

Six months later. So far, four rejections from publishers. Couched, mind you, in encouraging remarks:

“Believable characters … strong and powerful writing … gripping story … Judith has an exciting flair for plot … evocative descriptions.”

And then the death knell on my hopes.

“Unfortunately … our lists are full … we’ve just accepted a similar book … we are only a small company … I’m sure you’ll find a platform for Judith’s work … etc. etc.”

The self-doubt, the frustration, flooded back.

Then the call from the agent; ‘I think it’s time to re-evaluate the comments we’ve had so far. Parts of the storyline need tweaking. I’ve negotiated a deal with a commercial editor. When she mentioned the sum I had to pay (yes, I had to pay, and yes, I was that naïve) I gasped.’ It’s a realistic charge by today’s standards,’ she said. ’Think about it. In the end we’ll have a book that will take you to the top of your field.’

I thought about it. Rejected the idea. Listened to advice from my various acquaintances. Thought about it some more. And then I rang the agent. ‘Okay,’ I said, ‘I’ll do it.’ I felt I had no choice; after all she was the expert. Wasn’t she? What did I know?

When the manuscript came back from the commercial editor, I didn’t recognise the story at all. ‘This isn’t what I wrote. It’s not my book,’ I told the agent. ‘It’s nothing like it.’ The plot, the characters had been completely changed.

‘You know nothing of the publishing world. If you want me to represent you, you have to listen to me,’ she insisted. ‘Do as I say.’

‘But …’

‘Take it or leave it.’

I consulted our daughter, luckily she’s a lawyer qualified in Intellectual Property.

‘You can cancel the contract within the year. After that, you have problems. There will be all manner of complications…’

I moved quickly. The agent and I parted company.

I took a chance and contacted Honno, the publisher who’d previously accepted two of my short stories for their anthologies. Would they have a look at the manuscript? They would. They did. Yes, it needed more work but…

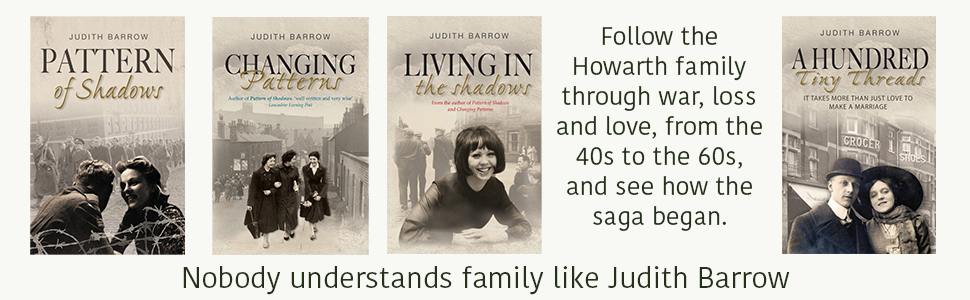

I’m proud to say I’ve now been with Honno, the longest standing independent women’s press in the UK, for fourteen years, and have had six books published by them. I love their motto “Great writing, great stories, great women “, and I love the friends I’ve made amongst the other women whose work they publish, and the support amongst us for our writing and our books. In normal times we often meet up. I’m hoping those “normal times” will return before too long.

Of course, there has been much editing and discussion with every manuscript. But at least, in the end, the stories are told in my words. With my voice.

Judith’s Writing Process

da-AL asked me to talk about my process of writing and, to be honest, it’s not something I’ve actually thought about before. But I’ve realised, with each of my books, it’s been slightly different. Not the time I write, I’m an early morning writer, always have been. I think waking around five in the morning is something I’ve done since childhood. Then I used to read, now I use the time to write. Usually until around eight or nine o’clock.

The pandemic and lockdowns have altered the pattern somewhat. The last few months have seen me at my desk more or less all day; I’ve managed to write two books. But I still start at five in the morning.

But back to the actual process; the usual question asked of authors is are they a plotter or a pantser. In other words, do they plot the whole book from start to finish, or do they just begin to write, and hope something happens to make an idea into a story — to have a plot in the end. I think I’ve been both in my novels.

My Haworth trilogy begins with a place I discovered — Glen Mill. It was the inspiration for the first of my trilogy: Pattern of Shadows. Glen Mill was one of the first two POW camps to be opened in Britain. A disused cotton mill in the North of England, built in 1903 it ceased production in 1938. At a time when all-purpose built camps were being used by the armed forces and there was no money available for POW build, Glen Mill was chosen for various reasons: it wasn’t near any military installations or seaports and it was far from the south and east of Britain, it was large and it was enclosed by a road and two mill reservoirs and, soon after it opened, by a railway line.

My parents worked in the local cotton mill. My mother was a winder (working on a machine that transferred the cotton off large cones onto small reels — bobbins — in order for the weavers to use to make the cloth). Well before the days of Health and Safety I would often go to wait for her to finish work on my way home from school. I remember the muffled boom of noise as I walked across the yard and the sudden clatter of so many different machines as I stepped through a small door cut into a great wooden door. I remember the women singing and shouting above the noise, the colours of the cotton and cloth — so bright and intricate. But above all I remember the smell: of oil, grease — and in the storage area — the lovely smell of the new material stored in bales and the feel of the cloth against my legs when I sat on them in the warehouse, reading until the siren hooted, announcing the end of the shift.

When I was reading about Glen Mill I wondered what kind of signal would have been used to separate parts of the day for all those men imprisoned there during WW2. I realised how different their days must have been from my memories of a mill. I wanted to write a story.

In Pattern of Shadows, and the subsequent two books, Glen mill (or Granville mill, as I renamed it) became the focus, the hub, and the memory of the place, around which the characters lived. The prequel, A Hundred Tint Threads, which I actually wrote after the series, was in answer to the many questions asked to me by readers; what were the parents of the protagonist, Mary Haworth, in the trilogy, like in their youth. With all four of these historical family sagas, I had a fair idea of the endings.

Unlike my previous books, The Memory, is more contemporary, and evolved as I wrote. The background stems from a journal I kept at a time when I was carer for my aunt, who lived with us. She developed dementia. Her illness haunted me long after she died, and the idea of the book was a slow burner that took me a long time to write, and I had no idea which way it would take me. It’s been described as a poignant story threaded with humour. I was thrilled when it was shortlisted for The Wales Book of the Year 2021 (The Rhys Davies Trust Fiction Award).

My latest book, The Heart Stone, was also a story that, in a way, wandered towards a denouement. Written during lockdown I allowed it to meander whichever way the characters took me. I was quite surprised by the ending.

All this being said, I realised that I do actually have a process of working. It comes automatically for me, so I haven’t actually thought it was a method. With every book I write, I research the era: what was happening in the world, what was on the newspapers, what work was there? What were the living/working conditions in the UK: the houses, the contents, the fashions, the music, films, radio or television, the toys, and books?

I always graph a family tree, with birthdays and dates of special occasions for each character. And, for each character I write a list: appearance, relationship to other characters, clothes, work, hobbies, habits, personality. Then I pin them to the noticeboard in front of my desk, so I am able to see everything at a glance.

So, I say to myself now, I do have a process… of sorts. I just don’t know if I’m going to plot an ending, or let things evolve until I begin writing. But I thank da-AL for giving me the chance to reflect on how I work. And I’d love to know what methods other writers use.

What method do you use to write? And do you have labels you like to go by?

[…] notes on my podcasting evolution: since author/blogger Judith Barrow contributed a guest blog post h-e-r-e about how she got published that I podcasted h-e-r-e, this week I produced a video version of it […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] on AnchorFM, where the most recent show is the audio rendition of my blog post (the blog version is h-e-r-e), “Xme + Publish: Barrow’s Trad + Podcast 3 Cotticollan’s […]

LikeLiked by 1 person